Nick Darmstaedter – Napster

Nick Darmstaedter

Napster

| (Past) | 26.02.201526.02.15 — 04.04.201504.04.15 |

|---|---|

| (Gallery) | Rue de Livourne 32 Livornostraat |

(01/05)Exhibition views

Napster

Napster was a peer-to-peer internet file-sharing service founded in 1999 by Shawn Fanning, an 18-year-old college dropout.

The website, which operated between 1999 and 2001, specialized in the exchange of MP3 music files via downloads,

attracting some 80 million users at its peak. Thousands of recorded songs could be illegally sourced from the Napster site,

voiding the financial royalties and copyright protection that should have been afforded to their musicians. As this capability

was offered free of charge, the program and its core concept precipitated one of the greatest commercial disruptions in

music industry history.

Barely a year after its release, lawsuits from major artists and record labels such as Sony and Universal had been filed

against Napster. Ultimately, a $26 million settlement by the Recording Industry Association of America forced the small

company of only 50 employees into bankruptcy in 2001. Although now under the ownership of Rhapsody, a subscription-only music program, Napster was the beginning of an idea that revolutionized the way information could be exchanged across the web. It has since given rise to countless services that utilize similar technology within and without the

boundaries of copyright law.

Nick Darmstaedter’s paintings are inspired by the cover designs of albums by musicians who, like Shawn Fanning, began

their careers on the fringes of the mainstream. The four albums referenced here, by Metallica, X, Capone-N-Noreaga, and

N.W.A. (Niggaz Wit Attitudes), were released between 1983 and 1997. Combining raw lyrics with an aggressive energy,

each of these artists evoked a hardcore mentality that sought to expose the harsh realities of everyday life and challenge

the way listeners thought about music.

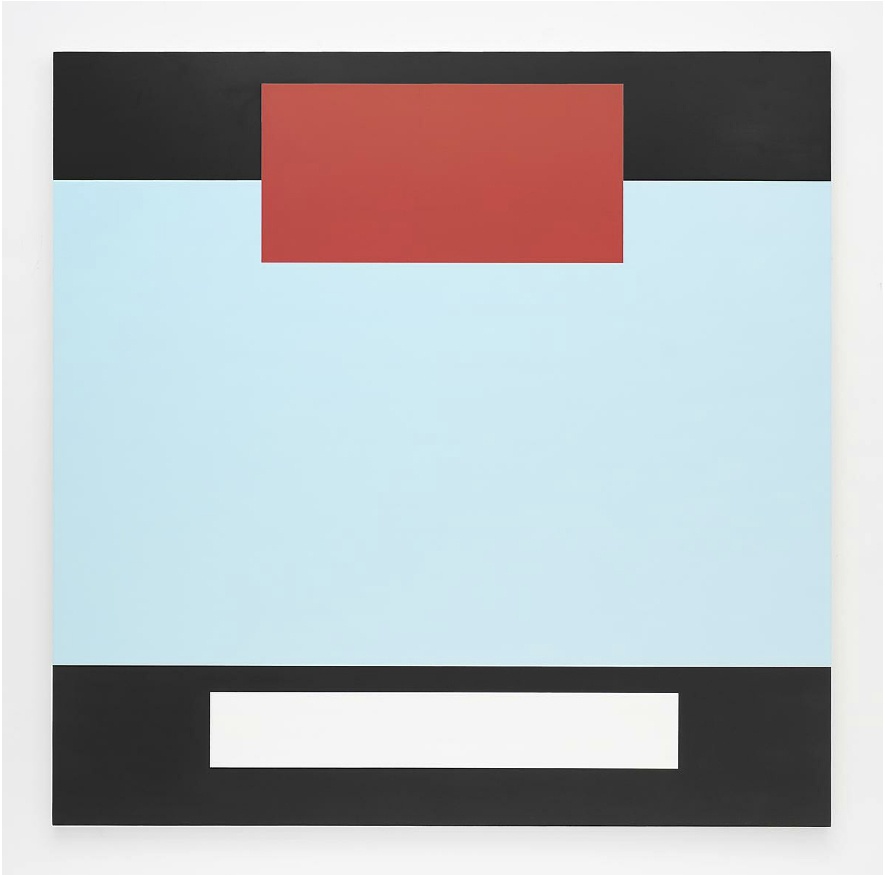

Darmstaedter’s flat, bright hues and minimal compositions are based on the original record packagings of these influential

albums. Translating their text and graphics into clean, precise form, the paintings sterilize the covers’ original imagery.

Detached from their intended content, the underlying designs of the albums are exposed for their formal delicacies. The

resulting works, carefully rendered in oil paint, are closer in appearance to the hard-edged American paintings of the late

1950’s and 60’s than they are to the album covers themselves. This particular type of painting was concentrated among a

group of painters in California who embraced the style in reaction to the gestural extravagance of the Abstract Expressionists before them. Here Darmstaedter gives a nod to art’s persistent recycling of past styles, propagating new movements that are eventually popularized and anointed with a brand name before their innovations are deemed exhausted and irrelevant by the next generation.

A parallel can be found with Metallica, X, Capone-N-Noreaga, and N.W.A., whose growingly popular hard core music

laid the groundwork for an eventual softening of their genres to mass appeal. Moving on to become highly successful and

wealthy artists as a result, the musicians left behind their gritty roots for lives of luxury. They became actors, married actors,

and started their own headphone business empires. In 2000, Metallica and Dr. Dre, a founding member of N.W.A., each

sued Napster, a small company offering an alternative to the corporate lifestyle that they had once disparaged in their

songs, after discovering that those songs had been made available for free.

By repositioning a historical, categorized style of painting in new light, Darmstaedter examines how the very idea of newness

is predicated on what has come before it. Movements, both in art and in music, are reactionary in that they are in

constant dialogue with the past. This has led many to believe that painting is an end game and that there will eventually be

nothing left for future artists to respond to. Darmstaedter’s paintings address this issue directly, demonstrating a faith in the

ability of abstraction to restore itself with the language of its own past for the very purpose of moving forward into the new.

Artworks

(04)-

![Nick Darmstaedter, Breathless]()

(Artist) Nick Darmstaedter (Title) Breathless (Year) 2014 (medium) Oil on canvas (Dimensions) 213.4 x 213.4 cm (Reference) NDar011 -

![Nick Darmstaedter, Compton]()

(Artist) Nick Darmstaedter (Title) Compton (Year) 2014 (medium) Oil on canvas (Dimensions) 213.4 x 213.4 cm (Reference) NDar012 -

![Nick Darmstaedter, Ride the Lightning]()

(Artist) Nick Darmstaedter (Title) Ride the Lightning (Year) 2014 (medium) Oil on canvas (Dimensions) 213.4 x 213.4 cm (Reference) NDar009 -

![Nick Darmstaedter, War Report]()

(Artist) Nick Darmstaedter (Title) War Report (Year) 2014 (medium) Oil on canvas (Dimensions) 213.4 x 213.4 cm (Reference) NDar010