Sally Ross – Material Matters

Sally Ross

Material Matters

| (Past) | 18.05.201918.05.19 — 06.07.201906.07.19 |

|---|---|

| (Gallery) | Rue de Livourne 35 Livornostraat |

(01/08)Exhibition views

Sally Ross: Clockwise

The story of painting is told and retold (as its own witness or as appropriation), each relying on memory, ours as well as that of the storyteller. It may be fictionalized or reportorial (abstraction, representation), may follow the contours of the everyday or the fluidity of the unconscious (realism, surrealism), even the awake dream, lost in thought by the light of day. It has protagonists, whether seen or unseen, hovering above the canvas (figuration, action painting), maps the space and situations they inhabit or haunt (a landscape, the picture plane), relies on or abandons plot structure (geometry, the monochrome), delivered by a narrator whose voice is resonant or elusive, sometimes using painting’s language and means to question itself: painting considered as both material witness and evidence.

Today, in post-time, the artist may freely interact with these engagements and devices, not having to take a side, or only in passing, shifting her point-of-view, and ours, recording and re-inventing her direct observation step-by-step, re-tracing her movement, allowing us to be there, simultaneously in the moment and after-the-fact, as the painting comes into being and goes on. It is in this sense alive. On the gallery wall it is finished but not yet done. We complete it in the act of seeing, and every time we look. We clearly apprehend its coming together. We will always notice something else. The paintings of Sally Ross are in the details. Parts to the whole.

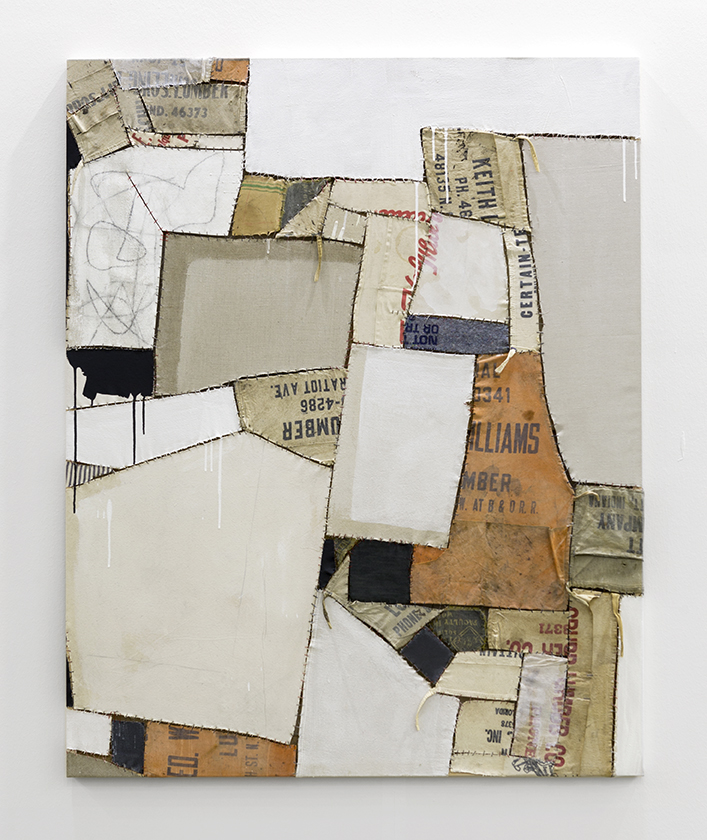

Ross first works on the floor, composing pieces of canvas, fabric, netting, bits of older paintings extracted and repurposed, to create a bigger picture, depending on its needs. As the pieces fall into place, she stitches them together with polyester thread. The stitching is open enough for us to see the spaces in between, and sometimes the wall behind, a jagged “drawing” technique that amplifies the hum of their construction. Ross’s work is heir to the experiments of the collage and combine artists, of Kurt Schwitters and Robert Rauschenberg, of the writers Brion Gysin and William Burroughts who pioneered the cut-up technique, a remaking of reality by chance operations, embracing the element of surprise for themselves as well as for the reader, allowing for otherwise unimaginable pictures in the mind’s eye. Ross, in her object-like topography, recalls the sculptural structures of Lee Bontecou. Ross’s points of reference and departure are not only Western, since her approach has been informed by the Gutai artists of Japan, by Yayoi Kusama’s enveloping, expansive nets, by the Italian arte povera artists, and by a willingness to disrupt or destroy the canvas demonstrated by Niki de Saint-Phalle: painting as target practice. (Ross has on a number of occasions shot a bow and arrow at paint-filled balloons attached to a canvas to create a spontaneous burst of color, an event without any direct recourse to the hand of the artist, only her aim, equally for her accuracy and her intention.) The sewn and interlocked elements that define her facture and fractured surface, a seismic landscape, are reminiscent of the work of Alberto Burri and Conrad Marca-Relli. Also important to her picture-making and breaking is Ross’s use of inscription. What the writer Mario Diacono has described as the abstract calligraphy in her paintings echoes the bold spatial strokes of Franz Kline, while her everyday observation of graffiti in and around New York subway trains and platforms is apparent, if not readily so, although once you see it, it’s there.

Even as many of the references we bring from historical figures and movements recall the 1950s/’60s (the artist was born in 1965), Ross’s work reanimates the radicality of painting from that exploratory era in ways that acknowledge the present, whether as an unfinished story, which is the story of painting, after all, or in terms of what painting can be and do, how it will actively perform, particularly in a period when it’s neither easy nor safe to trust the tale or the teller. There is a sincerity and a directness to the work of Sally Ross, her desire to include the viewer, an openness and generosity that parallels a need for, in her own words, “creating layers of space.” There are various entry points, ways in and around, an invitation to settle in there, to pleasurably lose and find our way. In the story of painting, no matter how recognizable or unrecognizable a picture appears, we admit that all art is artifice, but in this it is also a clear reflection of reality. One of Ross’s recent paintings is titled Dharma Bum, referring to the 1958 novel by the writer Jack Kerouac, The Dharma Bums, who played the Buddhist concept of an eternal, universal truth inherent to the nature of reality off of Beat transcendence, a nomadic state of body and mind. The bums, of course, are those seekers and wanderers moving from one place/experience to another, further along in life from the author’s On the Road, a key text in Beat culture, whose influence rippled out in many directions. What, Sally Ross may ask, given its history of restless turns and returns, is the inherent nature of painting? Her works move from place to place, investigate layers of reality, time-travel as it were, taking us with them.

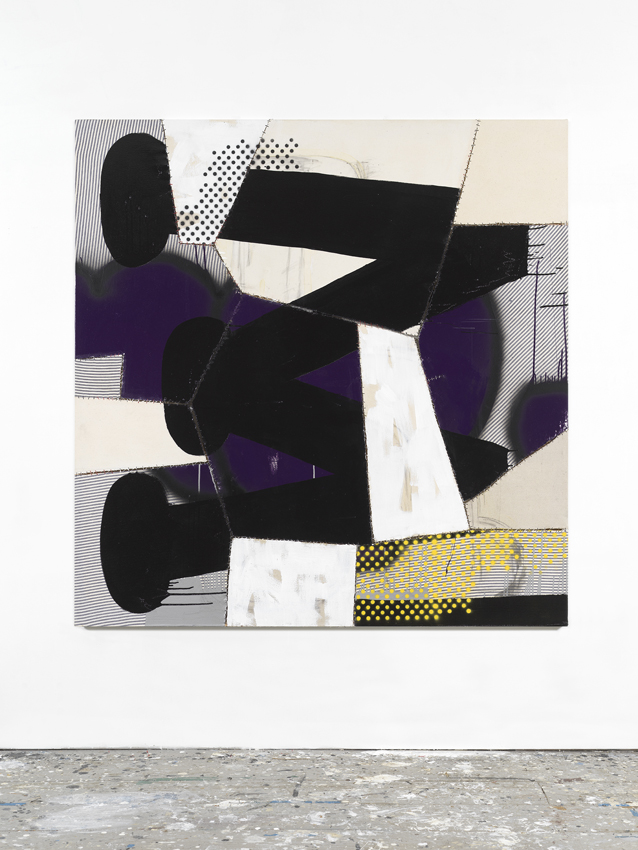

One new painting, Monkey Head, is the result of Ross’s usual process with slight turns of her orientation. Working on the floor she can look at a – composition as it unfolds from all four sides, deciding on its top and bottom, its left and right edges, where things will fall up, down or sideways, as the painting evolves and, in the case of Monkey Head, revolves. Looking at it in the studio, with its prominent M tilted to the right, Ross explains that every time she did something to the painting she would shift it clockwise and do something else. As spontaneous as the image appears, she would keep going back to the painting over a period of six months, and so despite the near-instantaneous expression it seems to be the result of, it was a half year in the making, and unmaking. The element of time—time as a material and a subject—is palpably present, her turns in every sense clockwise.

—Bob Nickas

Artworks

(06)-

![Sally Ross, Birdhouse Tango]()

(Artist) Sally Ross (Title) Birdhouse Tango (Year) 2019 (medium) Gesso, matte medium, enamel, spray paint, and flashe, on canvas, denim, printed fabric and wood, with polyester thread (Dimensions) 152.4 x 121.9 x 24.1 cm;

60 x 48 x 9 1/2 in(Reference) SRos008 -

![Sally Ross, Sugar Mountain]()

(Artist) Sally Ross (Title) Sugar Mountain (Year) 2019 (medium) Gesso, enamel, flashe, and acrylic on canvas, linen, and printed fabric, with polyester thread (Dimensions) 160 x 190.5 cm;

63 x 75 in(Reference) SRos005 -

![Sally Ross, Monkeyhead]()

(Artist) Sally Ross (Title) Monkeyhead (Year) 2018 (medium) Gesso, matte medium, enamel, spray paint, and graphite, on canvas and printed fabric with polyester thread (Dimensions) 172.7 x 167.6 cm;

68 x 66 in(Reference) SRos006 -

![Sally Ross, Walking Two]()

(Artist) Sally Ross (Title) Walking Two (Year) 2018 (medium) Gesso, oil, enamel, and epoxy resin on canvas and printed cotton, with polyester thread (Dimensions) 198.1 x 152.4 x 22.9 cm;

78 x 60 x 9 in(Reference) SRos001 -

![Sally Ross, Interrompante]()

(Artist) Sally Ross (Title) Interrompante (Year) 2018 (medium) Gesso, matte medium, enamel, spray paint, and flashe, on canvas and linen with polyester thread (Dimensions) 142 x 152 cm;

55 7/8 x 59 7/8 in(Reference) SRos009 -

![Sally Ross, Keith Lumber]()

(Artist) Sally Ross (Title) Keith Lumber (Year) 2018 (medium) Gesso, enamel, and graphite on canvas and printed cotton, with polyester thread (Dimensions) 152.4 x 121.9 cm;

60 x 48 in(Reference) SRos002